“All I Think About With That Dish Is My Mum.”

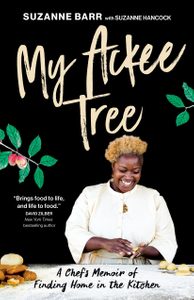

In this excerpt from My Ackee Tree, author and chef Suzanne Barr shares her memories of cooking with her family and the Caribbean staples they bonded over.

My parents didn’t make a conscious effort to teach me how to cook. They were just cooking all the time, and I was there watching. Staring at my mother’s hands around that bowl.

—

The sky was always blue in Florida. Royal, sapphire, Egyptian, olympic, electric. Tanya and I wanted seasons, to watch leaves fall in autumn and wear snow boots in winter. We sometimes shuffled through family photos of a life before, memories of winters in Toronto with our cousins before we moved to Florida. But the view out my window in Plantation was pretty constant. Blue from the sky and green from a tree that never changed.

The tree, though, was something special: ackee. Jamaica’s national fruit. The poor thing rarely fruited, but it was still like a Jamaican flag in front of our house.

Of all the jobs Mummy asked me to do in the kitchen, cleaning ackee was my favourite.

—

Returning home from a Caribbean market, Daddy places a whole sack of ackee on the table. Bright-red fruit peeks from the bag. Each pod is the size of Mummy’s palm, and they look like beautiful undersea flowers, opening.

Tanya and I stand beside her at the counter. “Don’t mash up de ackee.”

We roll our eyes. “We know, we know. You tell us every time.”

She sucks air through her teeth from behind pursed lips, then lets out a short, sharp kiss. It’s a technique my mum mastered before my time. Jamaicans are experts at kissing teeth.

A short kiss means minor irritation. A longer, deeper kiss means that Mummy is vexed. Kissing teeth can indicate annoyance, anger, and even joy…

It’s only a short kiss this time, and Mummy is showing us that she disapproves of our eye-rolling and our sass.

“Put the seeds here in this bowl.”

Her accent was subtle, but Jamaican Patois would shine when she was vexed, or when she was reminiscing with one of her friends.

“Cha” (no, man) was one of her staples.

“Cha, cant bada with de childe, pickney de too facety.”

Mummy had an arsenal of dialects and accents for everyday use.

I didn’t love the actual work of cleaning ackee—gently separating the fleshy parts of the fruit from the shiny black seeds—but I loved knowing that we’d have ackee and saltfish the next morning. Ackee has a mild flavour, kind of nutty, and a buttery texture that pairs perfectly with salted fish.

“This one isn’t open, Mummy.”

She grabs it out of my hand.

“It’s poisonous. The fumes will kill you,” she says.

It always shocked me, that fact. If it’s eaten too soon, before it opens on its own, it can be toxic.

She sifts through the bag, pulling out any closed pods, and places them on the marble windowsill above the sink. It’s where she puts tea bags she’s only used once, the kitchen sponge, her beloved spider plant.

Ackee flesh gets under my nails. It’s kind of slimy but not gooey. Firm yet soft to touch.

“It looks like a brain!” Tanya and I giggle. “

Cheeky innit! Stop playing with the food and finish up,” Mummy says firmly.

A seven-pound bag of ackee turns into one pound of flesh. Shells go in the garbage, black seeds are sprinkled in the backyard in hopes of another tree.

Cooking salt cod is a process. Mummy soaks the fish overnight in water, and then drains it the next day. She adds fresh water and brings it to a boil. The water spills over, and she kisses her teeth; she drains the water, boils it again, drains again, boils it for a third time, and drains it once more. Each time she changes the water, more salt is pulled from the fish.

When the fish is ready, she parboils the ackee flesh. Then she flakes the fish into big, succulent chunks and adds crispy sliced bacon, tomatoes, thyme, and scallions. Cooked ackee looks like scrambled eggs with its firm fluffiness and light-yellow hue.

There’s power and deep memories in that combination of flavours for me, and that’s why I rarely cook ackee and saltfish myself. It sits too heavy on my heart. All I think about with that dish is my mum.

Excerpted from My Ackee Tree by Suzanne Barr and Suzanne Hancock. Copyright © 2022 Suzanne Barr and Suzanne Hancock. Published by Penguin Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: This Rosemary Socca Is Best Served With a Glass of Rosé on a Summer Afternoon