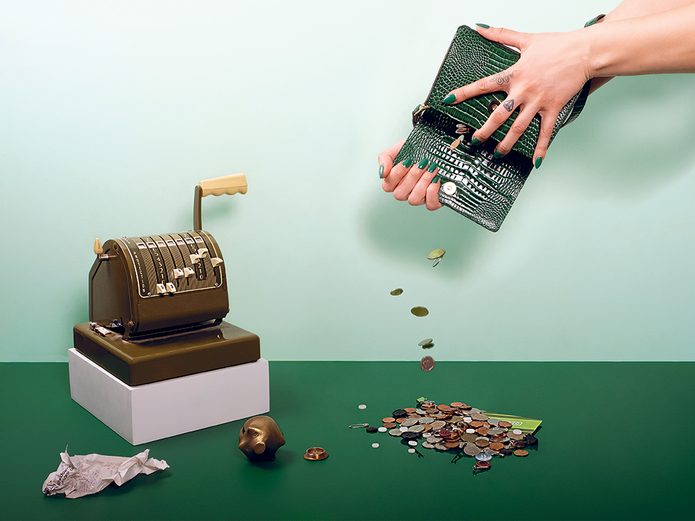

What Does a Post-COVID Economic Recovery Look Like for Women?

Throughout the pandemic, women have been 10 times as likely as men to fall out of the labour force. It’s hardly been a choice. With financial equity being the key to security, safety and better health, where do we go from here?

In the early months of 2020, as COVID-19 barrelled across the world, experts began to understand that this particular crisis was going to look a little lopsided. It was clear from the start that women would be the ones on the front lines of the pandemic. Here in Canada, women make up the vast majority of nurses (90 percent), respiratory therapists (75 percent) and personal support workers in long-term care and nursing homes (90 percent). They’re also far, far more likely to be behind the cash at a grocery store or cleaning hospitals, offices and schools. But as COVID’s economic impact came into focus, something else did, too: Women would be levelled by the financial fallout. And economists suspect the impact of this blow will be felt for years to come.

Typically, recessions hammer industries like manufacturing, construction and natural resources — sectors dominated by men. That’s what happened in 2008; it’s what happened back in the 1980s. When COVID arrived, though, it shut down all the industries that involve social contact: restaurants, retail, tourism, education, personal services, child care. Women disproportionately fill these workplaces, and they “were all effectively laid off in a single week,” says Katherine Scott, senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Over March and April 2020, more than 1.5 million women became unemployed. Among workers ages 25 to 54 — which is to say, most workers — twice as many women as men lost their jobs. In fact, after just several weeks of the pandemic, there were fewer women working in Canada than at any time over the past 30 years.

(Related: 8 Women Share the Impact the Pandemic Has Had on Their Mental Health)

But women didn’t lose only their jobs. With schools and child-care centres shuttered by COVID — plus babysitters, friends, neighbours and grandparents all off limits for fear of transmission — women lost their support systems as well. And, global pandemic or no, it’s abundantly clear who runs the unpaid economy. “Women still take on the majority of care work, whether that’s for children, elders or people with disabilities,” says Carmina Ravanera, a research associate at the University of Toronto Rotman School of Management’s Institute for Gender and the Economy. How much care work are we talking about? One study found Canadian women had upped their caregiving from 68 hours a week pre-pandemic to 95 hours during COVID — the equivalent of nearly two-and-a-half full-time jobs. Men averaged half that. So it’s no surprise who ends up leaving their employment to look after their families: In the first year of the pandemic, 12 times as many mothers as fathers quit their jobs to take care of toddlers or school-age children. Single mothers were even more likely to stop working.

All told, in Canada, women have been 10 times as likely as men to fall out of the labour force, which means they’re no longer looking for employment. It’s hardly a choice. After months — now more than a year — of home-schooling and caretaking and meal planning and Zoom meetings and working and cooking and cleaning and lockdown, something had to give. “I am gobsmacked by the number of women I know who are just at their end and can’t do it anymore,” Scott says. “That kind of churn is really damaging. But the expectation continues that women will drop out, absorb all this unpaid work and alone bear the long-term economic consequences of walking away.”

(Related: How Are Canadian Caregivers Handling COVID?)

—

At the start of the pandemic, as the world locked down and celebrities were crooning “Imagine” into their iPhones, we heard a lot about how COVID-19 was “the great equalizer.” The virus didn’t care about socio-economic status, the reasoning went, and besides, every one of us has been undone by all this upheaval and isolation. Even Ellen joked that being stuck inside — stuck inside her five-bedroom, 12-bathroom, pool-and-tennis-court-equipped California mansion — is just like being in jail!

Of course, COVID didn’t do away with inequality. It accelerated the inequality that already existed. Plenty of workers didn’t skip a paycheque or mortgage payment when the pandemic hit. “Not only that, they sat at home and watched as they racked up savings and their assets appreciated, because it’s been one of those crazy years in the housing market,” Scott says. Men are overrepresented in the scientific, professional and technical industries, which fairly seamlessly shifted to remote work. And as e-commerce boomed, these same sectors actually added 55,000 new jobs between February and October 2020 — three-quarters of which went to men. “For some people, this hasn’t really been a recession at all,” Scott says. “It’s quite a K-shaped recovery.” That’s the term economists use for a wildly uneven economic trajectory: Those at the top grow wealthier, while those on the bottom sink further into debt. But here, too, inequality persists; not all women are struggling the same way. “The pandemic has really affected those who are already marginalized in society,” Ravanera says. “So, broadly, women are leaving the labour force in large numbers, but we’ve seen that racialized and low-income women have been even more affected.”

(Related: What We Should Take Away From The Year of Covid)

Since February 2020, employment losses have been largest for people who earn the least — a group that’s overwhelmingly made up of racialized women. Nearly 60 percent of women making $14 or less (that’s the lowest 10 percent of earners) were laid off or had the majority of their hours cut between February and April of last year. Even among all female earners, racialized women were hit harder: Nine months into the pandemic, the unemployment rate for minority women stood at 10.5 percent, compared to 6.2 percent for white women. For Black women, it was higher: 13.4 percent. For Indigenous women, higher still, averaging 16.8 percent from June to August 2020. “Racialized and low-income women are disproportionately concentrated in roles that are not well-protected, that don’t have paid sick leave,” Ravanera says. “So they’re more likely to contract the virus, they’re more likely to have to choose between their health and their work, and they’re facing higher rates of unemployment.”

And the implications of that loss will stretch long past the end of this pandemic. “The rent wasn’t cancelled — it was deferred,” Scott says. “We’re looking at large debts coming out of COVID, and it’ll take people years, if not decades, to climb out of that hole. That impacts not only their security but the security of their family and kids, and whether these young people are going to be able to go to post-secondary school.” In Canada, women are more likely to carry student debt than men are; they’re more likely to owe more money than men do; and they’re much more likely to file for insolvency based on that debt. “It just reinforces disadvantage,” Scott says. “It really drives the wedge.”

No wonder, then, that this pandemic is wreaking havoc on women’s health as well as their wallets. “Financial strain — not being able to put food on the table, not being able to pay your monthly bills — contributes to ongoing stress and has a negative effect on people’s mental health,” says Dr. Samantha Wells, senior director at the Institute for Mental Health Policy Research at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). A report released at the start of 2021 from Leger and the Association for Canadian Studies found that over 40 percent of unemployed women surveyed described the state of their mental health during COVID as “bad or very bad.” (Just over a quarter of unemployed men said the same.) And during the pandemic, CAMH found women in general more likely than men to suffer increased anxiety and depressive symptoms.

It’s one more way COVID has compounded inequality that already exists. “We know that women experience higher levels of anxiety and depression than men do,” Wells says. We knew that before the pandemic — in fact, those levels are twice as high. “So of course women were hit terribly hard. You see that in the numbers.” But you also hear it — really, really hear it — when you talk to your friends and family and colleagues and neighbours and, very likely, when you stop for a nanosecond to check in with yourself. Adds Wells, “You hear it when women tell the story of how overwhelmed they are.”

(Related: Going the Distance: How Covid Has Remapped Friendships)

As the pandemic barrelled toward its first anniversary, an RBC report offered grim news: Nearly half a million Canadian women who’d lost their jobs still hadn’t returned to work as of January 2021, and 349,000 hadn’t returned as of February. There’s always a concern that people who step away from the labour force will have a more difficult time getting back in; we’ve seen that with the so-called mommy penalty, where women experience a significant drop in their earnings for five full years after the birth of a child. But COVID’s sheer unpredictability complicates matters further. “There’s so much that is unknowable, including how quickly the economy will get back into full gear and our appetite to return to the way things were,” says Dawn Desjardins, deputy chief economist at RBC and one of the authors of the report. Will people want to eat in restaurants? Browse the shelves of tiny shops? Drop their kids off at daycare or put their parents in long-term care homes? “I don’t know whether that bounces straight back,” she says.

Nor does Desjardins know what the demand for labour will look like once this pandemic actually ends. Even before COVID, women’s jobs faced a higher risk from automation, as AI made inroads into the services sector. Back in March 2019, another RBC report determined that women held 54 percent of the positions that were highly likely to be automated. That shakes out to 3.4 million jobs. And now? “The pandemic has accelerated the digitization of business and e-commerce,” Desjardins says. “Will we need fewer people for that face-to-face contact? People have certainly become more accustomed to ordering their groceries or their clothes online.”

(Related: Covid, One Year Later: How to Move Ahead When the Tank Feels Empty)

So what needs to happen here? In his September Throne Speech, Justin Trudeau acknowledged that women, particularly low-income women, had been hit hardest by the pandemic, and in March of this year — just in time for International Women’s Day — Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland announced the creation of a female-led economic task force. A long-promised national child-care program seems closer to becoming a reality, which pretty much every economic expert will tell you is table stakes. “The old approach to recovery, which is throwing money at guys in hard hats, is really not going to cut it this time,” Katherine Scott says. “Child care is absolutely critical.”

Beyond that, mandatory paid sick leave for all workers — including part-time, low-wage and hourly workers — is a no-brainer. (How are we still debating this in the middle of a pandemic?) So is setting a higher minimum wage. And so is understanding that these issues won’t magically disappear once we all manage to get our COVID vaccines. For all the talk of these unprecedented times, there’s lots of evidence to suggest women’s labour, both paid and unpaid, has been deeply undervalued. And there’s plenty of data to show racialized workers aren’t given the protection they’re due.

That’s why any recovery plan needs to have equity at its centre, and why the people hit hardest by COVID’s fallout need to have the most say in the response. “The cracks in our society’s foundation have made us even more vulnerable to crises like this, and if we don’t focus on who is most impacted, then those circumstances are going to continue,” Carmina Ravanera says. “Structural changes need to be put in place so that the recovery we have is long-lasting — and so marginalized groups don’t face the brunt of a downturn like this one again.”

Next, read about a death doula’s experience working during COVID.