The fight against breast cancer

World-renowned cancer Researcher Tak Mak says that if you had asked him just three years ago how he felt about the future of breast cancer research, his answer would have been, “Depressed.” But today? “Excited.”

What has changed is that researchers are looking at new and promising approaches to treating cancer, says Mak, director of The Campbell Family Institute for Breast Cancer Research at Toronto’s Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, one of the top five cancer research centres in the world. For decades we have relied on chemotherapy drugs that attack some fast-dividing cells, including both cancerous ones and healthy ones such as those found in the hair, digestive system and blood-producing parts of bone marrow. That’s why these effective but toxic drugs cause hair loss, nausea and infection.

Mak and other researchers have found that cancer cells share some similar traits, such as metabolic changes, regardless of the type of cancer. As you read this, Mak and his team are developing sharpshooter drugs designed not to kill cancer cells but to destroy the enzyme that allows them to reproduce. One drug is currently in clinical trials to test for its toxicity on women who have basal breast cancer, a particularly insidious and difficult-to-treat form. If successful, the drug may have implications for other cancers, too.

Radiation therapy is also changing. A technique called intra-operative radiation therapy (IORT), developed in Japan in the 1970s, was the focus in 2013 of a long-term study published in The Lancet that showed the results are similar to standard radiation therapy. IORT involves a single, one-time dose delivered inside the breast during surgery, eliminating the need for the standard five treatments a week over three to six weeks. It also dramatically reduces side effects and saves patients time. So far, IORT is available to post-menopausal women with early-stage tumours, and is offered in Canada at Princess Margaret as well as the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal.

Here is what’s on the horizon:

• Researchers in the U.K. are developing a simple blood test that could predict breast cancer five to 10 years before it could be detected by mammography.

• More women will take Herceptin, a drug Mak estimates has already benefited half a million women worldwide with advanced and early HER2-positive breast cancers.

• Scientists are looking at the role that “good” and “bad” gut bacteria (each of us carries three to five pounds of the stuff) play in immunity, focusing on inflammation. Research shows a correlation between too much “bad” bacteria and inflammation, a risk factor for chronic diseases such as cancer. “Inflammation is the future of medical research,” Mak predicts.

One in nine Canadian women will develop the disease in her lifetime-but the five-year survival rate is now at an all-time high of 88 percent. Breast cancer mortality rates have fallen by 42 percent since the peak in 1986, thanks to earlier detection and improved treatments.

We spoke to four women who not only survived the trauma of breast cancer but whose lives have gone in fresh and unexpected directions. These women offer inspiration to anyone facing this diagnosis. Click through to read their courageous stories of survival.

Pictured: Breast cancer survivor Janelle Blair and her daughter Zara. (Lee Weston Photography)

Janelle Blair

Diagnosed at age 29 with an aggressive form of breast cancer, Janelle Blair of Toronto, now 35, had just finished chemotherapy and was about to start radiation. “I had no hair, no eyebrows and I looked very pale-I was not very attractive!” she recalls. And that’s when her boyfriend proposed to her.

Her now-husband, Karim, was the one who first noticed the lump; he urged Blair to go to the doctor. “I thought, if he wants to marry me now, it must be for the right reasons,” she says. The wedding planning was something positive for people to ask her about, instead of always asking about her health. The couple waited a year and a half- “I wanted to have hair, be healthier and feel normal”-and then tied the knot in the Bahamas with 70 guests.

Blair, a production manager with Global’s ET Canada, wanted children. But first she had to have the standard hormone therapy for her estrogen receptor-positive cancer, using the drug tamoxifen, which blocks the effects of estrogen on breast cancer cells but can also cause birth defects. When she decided to come off tamoxifen three years later to get pregnant (standard treatment is five years), her oncologist sent her to a fertility specialist. There was bad news. Her likelihood of getting pregnant was low: Chemotherapy had depleted her egg supply; endometriosis had blocked one Fallopian tube; and as a breast cancer survivor she was a poor candidate for fertility drugs. “That night I cried more than I ever had over breast cancer,” Blair recalls.

Unwilling to give up, she charted her ovulation cycle religiously, consulted a Chinese medicine doctor and tried acupuncture. Within a few months she was shockingly, ecstatically, pregnant. Today, Blair is the mother of one-year-old Zara. “Every time I look at my daughter, I feel so lucky.”

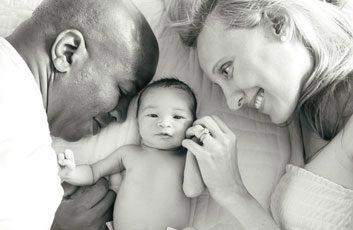

Pictured: Blair with her husband, Karim, who went with Blair to every doctor’s appointment after her diagnosis. (Lee Weston Photography)

Sarvjeet Mangat

Sarvjeet Mangat had never even heard of breast cancer until she was diagnosed with it six years ago at age 46. She had immigrated to Brampton, Ont., just a few years earlier with her two children and husband from a village northeast of Delhi, India, and dismissed her breast lump as an irritation from her bra. Several months later, when the lump grew, she confided in her then-17-year-old daughter, Baljot, who, along with her father and brother, urged her mom to go to the doctor. When the diagnosis came with the word “cancer,” Sarvjeet says, “I was terrified.” The whole family cried, presuming it was a death sentence.

But then Internet-savvy daughter Baljot decided to do some research to add to the information the hospital had given them. She found that breast cancer is treatable, and conveyed that to her family.

Still, in their South Asian community, breast cancer was shrouded in secrecy and stigma. Sarvjeet felt ashamed after losing her long, thick hair, a symbol of Indian beauty. Some people kept their distance, believing cancer to be contagious. Well-meaning relatives and friends called with misguided advice. One commented, “You shouldn’t have let the doctor touch your breasts.” Another said, “You should have gone to India to a natural healer.”

Sarvjeet underwent a lumpectomy, chemotherapy and radiation. She has now finished five years of hormone therapy and today has a very good prognosis.

While still in high school, Baljot decided to raise awareness in her community, and handed out flyers about breast cancer written in Punjabi and English. Some people threw it back at her, but others read it. In speaking with people, Baljot discovered that some women were keeping their breast cancer a secret even from their husbands and families.

Baljot organized a walk-a-thon that she called “I Rock Pink Walk-a-Thon: Fight Breast Cancer” and raised $7,000. Since 2009, the non-profit has raised more than $85,000, with money going to charities including the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation and Aga Khan Foundation Canada. This past spring, she completed her thesis on cultural perceptions of breast cancer and titled her paper, “I Am a Punjabi Woman & I Have Boobs!” Now 23 and a manager for a bank, Baljot says, “I don’t want other families to go through what we did.”

Both parents support their daughter’s efforts. As her mom says, “You get nothing out of fear. It’s important to get checked and take control of your health.”

Pictured: Mangat surrounded by her family: daughter Baljot, son Gurvinder and husband Parminder.

Jenn McCrea

Tens of thousands of women across the country may stand to benefit financially from the activism of breast cancer survivor and “warrior mom” Jenn McCrea of Calgary. McCrea, 37, has helped launch a $450 million class action lawsuit against the federal government, intended to compensate mothers who have been denied employment insurance sickness benefits while on maternity leave. Even though Ottawa amended the legislation in 2002 to allow new moms with serious illness to collect sickness benefits during their mat leaves, many women, including McCrea, have had their claims denied. “I still have a lot of fight in me,” says McCrea, who is now deemed cancer-free, “and I can do this for other women who may not have the energy.” She believes the EI Commission has not fully implemented Ottawa’s amendments and has interpreted the legislation very narrowly, giving sickness benefits only to those who become ill during pregnancy and not during parental leave.

McCrea was inspired to take up the fight when she heard about Toronto mother Natalya Rougas, who was diagnosed with breast cancer during her maternity leave and in 2011 successfully battled to win sickness benefits totalling about $6,000.

At age 27, McCrea, who has a strong family history of ovarian and breast cancer, tested positive for BRCA1 (the “Angelina Jolie” gene mutation that is a ticking time bomb for ovarian and breast cancers). Knowing that she would have to have her ovaries out by age 35 at the latest, McCrea and her husband proceeded to have two children. Focused as she was on ovarian cancer, the mom of two boys was stunned to learn that she had breast cancer. While it was at the earliest possible stage, her best chance for survival was a bilateral mastectomy.

McCrea says her husband was endearingly supportive. “He said, ‘We don’t need your breasts. We need you.'” She underwent the surgery and was home the next day; the following year, she had breast reconstruction. Of her scars, she says, “I’m alive today because I have those scars. I choose to let them empower me.”

In addition to her public activism, McCrea, a part-time office manager, has logged some impressive personal accomplishments. Soon after her double mastectomy, though she’d never been an athlete and couldn’t run more than a block, she started training for a 5K CIBC Run for the Cure event. “Every step of that journey, I was proving something to my breast cancer,” she says. She has done many races since then. Last summer, she completed the Calgary Ironman, a triathlon that includes a 1.9-kilometre swim, 90-kilometre bike ride and 21.1-kilometre run.

Pictured: McCrea with her young sons Logan, 3, and MJ, 5.

Kelly Hennessey

Kelly Hennessey of Dartmouth, N.S., had resigned herself to the necessity of a mastectomy after being diagnosed with breast cancer in one breast, but she assumed she would receive breast reconstruction immediately afterwards. “I thought, you lose a breast, you get a new one,” says Hennessey. She was dismayed to learn that the standard wait in her area for reconstruction would be two years.

Hennessey, then 45 and owner of a public relations business, didn’t accept that. “I was stunned, I was shaking and I was very passionate,” she recalls. “I thought it was ridiculous that I couldn’t see a plastic surgeon and arrange to have my mastectomy and reconstruction at the same time.” She felt it would bring back a sense of normalcy to her life.

Her oncologist agreed (although not all radiologists or plastic surgeons would, because of complications that can arise), and referred her to a plastic surgeon. Seven weeks later, she had an eight-hour surgery to remove the cancerous breast and, in the same operation, build a new one using the DIEP flap technique. This method creates a new breast using skin and fat removed from the abdomen, as in a tummy tuck. “After the surgery, my stomach was flat as a table,” says Hennessey, the mother of three children.

Six months later, she opted to have the other, healthy breast removed so she would never get breast cancer again. This time she opted for a lat flap, in which the latissimus dorsi muscle is moved from the upper back. In that operation, extra skin from the hip was used to fashion a nipple on each breast. Hennessey has not yet had the nipples tattooed a darker colour (in Nova Scotia, the cost is not covered). She jokes, “I have Barbie boobs-all the same colour.”

Hennessey, 52, is happy with her breasts today. She says that although plastic surgery gets a bad rap as the domain of shallow celebs, it played a crucial role in allowing her to get on with her life. “Putting that missing breast back in a bra means a woman can return to her life. Returning to normalcy is the gift of breast reconstruction,” she says. Her experience motivated her to do volunteer PR for Halifax BRA (Breast Reconstruction Awareness) Day, an international event that helps women who need reconstruction understand how to navigate the healthcare system (this year it is Oct. 15). “Not a day goes by that I don’t celebrate my body, which I enjoy in a way I didn’t for the first 45 years of my life.”

Pictured: Hennessey, second from right, with her husband and children at Peggy’s Cove, N.S. From left: Jack, Kate, husband Sean and Patrick.