How an anonymous stem cell donation saved one boy’s life

At any given time, more than 1,000 Canadians are waiting for a stem cell donation. Read about one family’s inspiring story

Source: Web exclusive: May 2015

Donna Leith-Gudbranson, a 54-year-old Ottawa mother of four, had never heard of stem cell donations until her six-year-old son Dennis was diagnosed with cancer in the spring of 2004. A few weeks after having minor surgery to ease a chronic ear infection, some of Dennis’ blood work came back with worrying results. On the advice of his doctor, Leith-Gudbranson took her son to the hospital immediately, where medical staff ran tests for hours. Later that same day, her son was put on a gurney and wheeled up to the fourth floor: the oncology ward. It was a moment that still brings her to tears.

‘I literally grabbed the gurney and tried to stop it,’ she says. ‘I just didn’t want it to be true.’

Dennis was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, a type of blood cancer that has between a 60 and 70 percent chance of survival within five years if diagnosed before the age of 15, according to Cancer Research UK. He went into remission after five rounds of chemotherapy, but a few months later the cancer was back and this time doctors told the family his only chance for survival was a stem cell transplant.

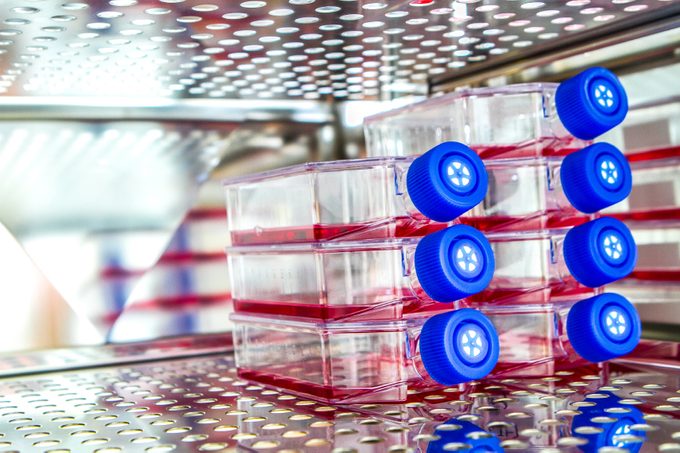

Stem cells are the body’s renewable ‘building blocks’ that can grow into any cell in the human body. Stem cells found in bone marrow grow into red blood cells, white blood cells or platelets, a type of cell that helps stop bleeding, says Dr. Ann Woolfrey, a medical doctor and researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, where bone marrow transplantation was first pioneered.

‘We’re talking about the cells that are kind of the ‘mother’ cells that generate all of the cells to make up a new, healthy bone marrow,’ she says.

These are also found in umbilical cords and can be forced into a donor’s bloodstream using growth factors ‘ a natural protein that stimulates cell production ‘ to be collected for a transplant, Dr. Woolfrey says.

Bone marrow stem cells can be used to treat multiple rare and life-threatening diseases from lymphoma to Sickle Cell disease. Healthy donor stem cells grow and replace the malignant or malformed blood cells in the sick person’s body, according to Dr. Woolfrey.

After Dennis’ initial diagnosis, Leith-Gudbranson, Dennis’ siblings and his father were all tested in case he needed a stem cell transplant down the line; they weren’t a match.

The likelihood of a full match within a family is about one in four for each family member, according to Dr. Chris Bredeson, the head of malignant hematology and stem cell transplants at The Ottawa Hospital.

‘But it’s not additive,’ he explains. ‘So, if you have two siblings, it’s not a one in two chance, it’s one in four for the first person and one in four for the second person.’

Because of these odds, only about 30 percent of patients are able to find a full match from a relative, he says. The rest, like Dennis’ family, have to hope for a stranger to be found through OneMatch, a division of Canadian Blood Services and the country’s arm of the international stem cell donor registry.

They were some of the lucky ones: after almost three months of waiting and living at the hospital with her son, Leith-Gudbranson received a call one morning from the oncologist with life-changing news.

‘She said ‘we’ve found a match,” Leith-Gudbranson recalls. ‘I screeched, of course. I literally ran up and down the hall of the hospital ward, yelling ‘we found a stem cell match!”

Now, more than 10 years after his initial cancer diagnosis, Dennis is a happy, healthy teenage boy ‘ Leith-Gudbranson jokes that she never thought she’d be so overjoyed to have a typical teen stomping around the house. He recently turned 18 and is heading to Concordia University in the fall to study finance. Dennis has been in remission for more than five years, which his mother happily declares is officially considered cured. The anonymous stem cell donation saved her son’s life.

In Canada, there are about 1,000 people waiting to find a stem cell donor match at any given time, according to OneMatch. Donors get on the registry by signing up online or at a donor awareness event and collecting a saliva swab using an at-home kit, which is mailed in to the registry. If they’re found to be a match, the donor will be contacted and can decide whether or not to donate. If they agree, the stem cells can be collected one of two ways.

The less invasive and more common procedure is for the cells to be extracted from the bloodstream; this is called peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Donors take growth factors to stimulate the stem cells to circulate through their bloodstream. After that, it’s a process similar to donating blood, explains Dr. Woolfrey: an I.V. is hooked up to the donor’s arms, blood is drawn, a machine skims out the stem cells and the blood is then pumped back into the donor’s body so they don’t lose too much. The process can usually be completed in one trip to the hospital, according to Dr. Woolfrey, and side effects are minimal. Currently, this method accounts for up to 80 percent of all unrelated stem cell transplants, according to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, a United States-based research facility that collects bone marrow transplant data from hospitals around the world.

The second, more well-known procedure is a surgery performed to extract the stem cells from bone marrow in the donor’s hip bone while under anaesthetic. There are a lot of misconceptions about the process and many people shy away from registering to become a donor out of fear that the procedure is painful or requires a nasty needle, according to Dr. Sheila Wijayasinghe, a staff physician at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto who has had patients treated using stem cell transplants.

‘People generally want to help but because it hurts, potentially, and because it’s a little bit more invasive I think there’s a little bit of hesitancy in that,’ she said.

But according to one donor who has been through the procedure, the side effects are no worse than a mild case of the flu.

‘It’s not painful. In the area [where they extract the stem cells] you feel a little sore and you feel tired. You’re feeling weak,’ said Andy Law, a 35-year-old banker from Toronto.

Law registered with OneMatch after his sister encouraged him to do so ‘ she had learned about the need for donors and enlisted friends and family to sign up.

A few months later, he got the call that he was a match. Law’s donation was made through the bone marrow method, which required surgery. Though doctors often opt for the less-invasive peripheral blood method, it does come with a slightly higher risk of complications such as Graft versus Host disease, according to Dr. Woolfrey. In some cases, these risks outweigh the benefits of the stem cells and so bone marrow transplants would be preferred, she said.

After the surgery, Law says he was up and about in a few days and fully recovered in two weeks, without so much as a lasting scar.

He said the trade-off of a few days of aches and fatigue was worth the knowledge that he likely saved someone’s life.

‘When you think about it, that two weeks of your inconvenience can extend someone’s life. You can save somebody.’

There is a special need in Canada and across the globe for stem cell donors of diverse backgrounds, according to Dr. Bredeson. Stem cells are better matched between people of the same ethnicity, he explained, because we inherit a kind of coding on our cells through our DNA called HLA antigens and these are used to match stem cells. People with similar ancestry are more likely to share HLAs.

Currently, about 70 percent of donors on Canada’s registry are Caucasian, according to OneMatch, so there is a dearth of available donors for patients with other backgrounds.

‘When we have such a diverse population as we do in Canada, the larger the numbers are in our bank the higher chance of actually matching. We have people coming from all over the world. We’re such a diverse community. Really, that’s an area that we need to work on,’ says Dr. Wijayasinghe.

There’s also a greater need for young, male donors because they tend to have more stem cells than women or older donors and are less prone to complications, according to Dr. Bredeson.

‘We’re trying to get as many cells as we can when somebody donates because the higher the cell count donated, the more likely and more efficiently the cells are going to grow in the recipient,’ he says.

Women are also generally preferred less as donors because if they have had children there’s a chance they could have immune cells when they donate that would react against the recipient, Dr. Bredeson says. But there’s another way some women can contribute: donating their child’s umbilical cord.

Umbilical cords are a rich source of stem cells that for generations were simply discarded as medical waste. Canada started a national cord blood bank in 2013 ‘ the last G8 country to do so ‘ to preserve stem cells from umbilical cords at participating hospitals in Ottawa, Brampton, Edmonton and Vancouver. These stem cells are then made available to patients around the world. Advocates ‘ including Leith-Gudbranson who works on the Ottawa donation campaign for the bank ‘ are fundraising and hoping to expand the number of hospitals that take part in Canada.

It’s the easiest way to donate, said Leith-Gudbranson and, as she knows first hand, can be one of the easiest ways to save a life.

‘Right now all of those stem cells are medical waste and it breaks my heart when I hear that,’ she says. ‘When a child is born, the mother can give life not once, but twice.’