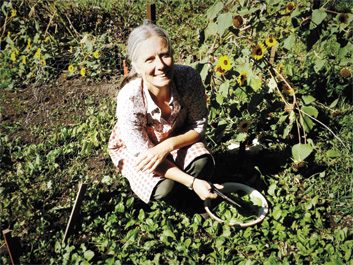

How one woman became a farmer

Thinking of trading in city life for the country? Here’s how one suburban woman started a successful farm

Source: Best Health magazine, Summer 2013; Image: Grant D. Black

As a spoiled ex-suburbanite from Winnipeg, I’m better schooled in mall crawling than horticulture. During high school, my vocational aptitude tests always resulted in the same two options: (a) teacher or (b) journalist.

‘Vegetable farmer’ wasn’t even listed as a possible career trajectory. Farming was considered career suicide for ambitious Winnipeg high-school graduates. If it hadn’t been for my sodbuster hubby, Grant, I never would have considered farming as a seasonal vocation.

Grant has farm roots on both sides of his Saskatchewan family tree. His maternal great-grandfather, Albert Cook, tended the gardens at Buckingham Palace, where he met Grant’s great-grandmother, a salad maid. In 1912, when the Cooks immigrated to Manitoba, they started a market garden. The land was cheap but it was too far from a large population centre to succeed. To make ends meet, Albert took up bear-napping cubs from local bear dens to sell to the zoo. He died in the forest from pneumonia at age 47, and his wife and children moved to Saskatchewan. Three generations later, in the ’50s, Grant’s parents left farm life. Grant grew up in cities and studied communications in Vancouver, but honed his green thumb on a rented urban lot in East Vancouver. He and I eventually met in Calgary and in 2004, left for Wakaw, Sask. (pop. 1,000), in search of a place to write and garden together.

Planning a farm

In 2012’100 years after Grant’s ancestors immigrated to Canada to farm’we found ourselves hatching plans for our own farm. We decided to grow heirloom vegetables. Many heirloom seeds date back to the 19th century and are non-patented, non-treated, non-GMO. We planted seeds from vegetables that have been saved and reseeded for generations: carrots, spinach, potatoes, corn, beans, beets, radishes, tomatoes, chard, lettuce, mustard greens and zucchini. Everyone in our small town has more than one job, just like that film Local Hero where Gordon Urquhart is a publican and an accountant. In winter, Grant and I earn our bread from freelance writing and book projects, but after seven seasons of amateur growing, we wanted our three lots to pay. And so last year, our heirloom vegetable business, PayDirt Farm, was born.

We decided to forgo the farmers’ market model and instead chose a CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture) business model, where the harvest goes directly to customers. Members pay for a share of the crop at the season’s start. We sold 21 memberships: Each full-share PayDirt Farm member receives 100 pounds of produce for $400, and half-share members get 50 pounds for $250.

Our 8,000-square-foot garden is less than an hour northeast of Saskatoon (where our members reside). In a CSA model, members share the farmers’ risk and pay upfront for their seasonal share. Our only pressure would be to grow good veggies.

Growing enough food

Now I understand why farmers are so obsessed with weather forecasts. I used to toss and turn at night over rewrites, but now I’m concerned about how much produce the garden can kick out every two weeks to fill members’ shares; I don’t want to disappoint them. In April, as soon as the soil could be worked, we seeded early spinach and radish (and covered it with a frost blanket) for a June harvest. In order to keep our members in fresh salads, we reseeded every two weeks. We learned this technique, called Small Plot Intensive (SPIN) farming, from an e-book by Saskatoon-based urban-market gardeners Wally Satzewich and Gail Vandersteen.

Like all ventures, this new career has its pluses and minuses.

I love the independence of farming, but the responsibilities are heavier than a writing gig. Weeding a pesticide- and synthetic fertilizer’free garden is a constant effort, and we worked every day to keep it in check through summer 2012. After the Labour Day weekend, I regretfully put away my swimsuit. We live one kilometre from a lake, but I had worn it just once all summer.

Due to heavy spring rains earlier that year, the mosquitoes were bigger and more aggressive, and mercilessly attacked me both in the shade and when I was weeding in the heat of the midday sun.

I searched online for mosquito net hats, but decided to tough it out with DEET, long sleeves, long pants tucked into rubber boots and a kerchief lodged under my straw cowboy hat. I never used to sweat yields when I was merely putzing around our garden. Grant and I just ate what it produced, and we often had lettuce that went to seed before we could eat it all. Now I count heirloom Chioggia beets and stubby Parisienne carrots, and petition them to ‘Grow, baby, grow!’ so we have enough for everyone.

Keeping customers happy

On biweekly pick-up days, spanning from mid-June to late September, Grant and I spent four or five harried hours harvesting and packing orders in recycled cardboard liquor boxes and reusable cloth bags we bought for each member. Our Volvo V70 station wagon was crammed to the ceiling with boxes and two giant Coleman coolers. Once the car was packed, we would rush into Saskatoon, drop off a couple of orders to housebound mums and one night-shift nurse. Then we rushed over to the pick-up spot and waited patiently for our members over the next two hours.

They often arrived all at once, so it became a bit of a circus. We quickly learned to entertain the lineup: Grant handed out his homemade cranberry-flax cookies while I dispensed the vegetable shares. Our members were keen to try unfamiliar varieties such as rainbow chard, and asked great questions like, ‘Can I eat the beet greens, too?’ ‘Yes, you can,’ I’d tell them with a grin. Sauté them in olive oil and garlic and you have a vitamin A’rich side dish for your supper.

Farm-fresh eggs were a welcome addition to the CSA. We sourced them from Yari, a 10-year-old entrepreneur who was saving his egg money to buy goats. He’s too young to drive, so his busy mum, Zenia, made the egg drop-offs. Our members loved them and it bulked out the orders on the weeks our yields were down.

The challenges of farming

Grant went nuts planting heirloom tomato seedlings: The 300 plants rapidly dominated the north patch. Half were caged while the other half quickly needed staking. When we took a weekend off to go to a family reunion, the un-caged plants started to run all over the garden. The next week was spent untangling and staking errant plants, with a solemn promise to use a cage next year for every plant.

I went a bit overboard on the organic fertilizer, which meant our plants were Franken-huge. And the Rainbow Inca corn was so tall it blocked out the neighbour’s house. I waited all summer for the Children of the Corn to pop out and grab at me, scythes in hand.

Thanks to fertilizer and an abundance of sun and rain, the zucchini leaves were the size of serving platters, and their yellow and green fruit grew quickly to match. I couldn’t distribute some of the football-size fruit since they were too tough. ‘Feed it to the dog,’ the Wakaw postmistress suggested when I told her about my over-sized zuke problem. ‘They love it. I add rice and ground beef and my dog just laps it up.’ I made zucchini muffins for the members instead, and they enjoyed them on pickup day.

We faced some unexpected challenges in our first season. Thanks to a very cold and wet June, the spring-seeded peas were a complete wipeout. There wasn’t enough to share with everyone so I dedicated the sparse few to home use. The best producers were the mixed-lettuce varieties and the giant spinach, since they thrive in the colder spring weather.

‘We can’t feed our members just greens all summer,’ Grant announced in mid-July. ‘They’ll want root crops, too.’ But our poor germination rates in June meant the carrots and beets had to be seeded twice because the first seeding failed. We were way behind schedule. So we just kept handing out greens for most of June and July, and tried not to focus on the long faces when there were no carrots yet again. July was much hotter than June so the carrots and the beets did finally make an appearance’like late dinner guests.

The rewards of being a farmer

We had to wait until the third week of September to wind things up, but it was worth it. Our final drop-off included fresh corn, green and ripe tomatoes, zucchinis, Straight 8 cucumbers (thick, eight-inch-long cukes), lemon cucumbers (shaped like a lemon, and yellow in colour), fingerling potatoes, and purple and yellow carrots. To close off a challenging first summer, we also served hot cinnamon-apple juice, sourced from an abandoned tree, to accompany more baked zucchini treats.

Our first season, we grossed $7,000 in sales and supplied 20 households with our vegetables. Yet our CSA wasn’t done until we had made our last drop-off to PayDirt Farm Member #21: my mother, Betty, who lives in Interlake, north of Winnipeg. Our Thanksgiving dinner consisted of a local country chicken and roasted heirloom vegetables, grown by an unlikely farm girl.

This article was originally titled "An unlikely farm girl" in the September 2013 issue of Best Health. Subscribe today to get the full Best Health experience’and never miss an issue!